What Greenland's birds have seen

Part 2 of 2: Last days of Disko expedition ended on a low note for Kumlien.

Greenland has been coveted by colonists for a long time. The people who desire this land now haven’t come up with anything interesting or novel at all.

First it was the Norse—who arrived in the 9th century—and then it was the Danes and Norwegians in the 18th century. The earliest inhabitants of Greenland were the Inuit peoples who arrived around 2500 BCE. The Inuit people represent a vibrant culture today, including nearly 90 percent of the territory’s population. Denmark took over for good in 1814.

It may not be a surprise that Greenland is a stronghold for birds. At more than 800,000 square miles—bigger than Alaska—Greenland is home to almost unending rocky shores laden with innumerable seabirds including colonies of auks, puffins, skuas, eiders, and many others.

Those birds—and a few Danes and Inuits—are who greeted a young American naturalist, Ludwig Kumlien, when he arrived on a vessel named the Florence at Disko Island, Greenland, in July 1878. Kumlien had spent most of the previous year across the icy Davis Strait on Baffin Island as part of the Howgate Expedition. As you might recall, I wrote about Kumlien’s time on Baffin Island last week. While Kumlien seems a congenial fellow, the aims of the expedition were far from charitable or altruistic. It was essentially a scouting trip for colonization, orchestrated by an enigmatic figure named Henry Howgate, who remained stateside. Still, the 25-year-old Kumlien was fortunate to get to join the trip due to a connection with distinguished naturalist Spencer Baird and the Smithsonian Institution. Kumlien wasn’t someone necessarily of any means, but his father, Thure, was a taxidermist and natural historian who gained some renown because of his careful observations at Lake Koshkonong, Wisconsin.

Kumlien’s charge as an expedition naturalist was to identify new species, which was a somewhat lesser objective for what was essentially an economic trip for Howgate and U.S. interests. For Kumlien, the time on Baffin Island’s Cumberland Sound had been a bit of a dud, as he was icebound for months in a barren, rocky area that was mostly impassable. On Disko, though, things were looking up. The weather had broken for the brief Arctic summer and a re-supply ship was going to meet the crew. Further, Kumlien was greeted by Danes on Greenland who knew a thing or two about birds, namely Governor Edgar Fencker.

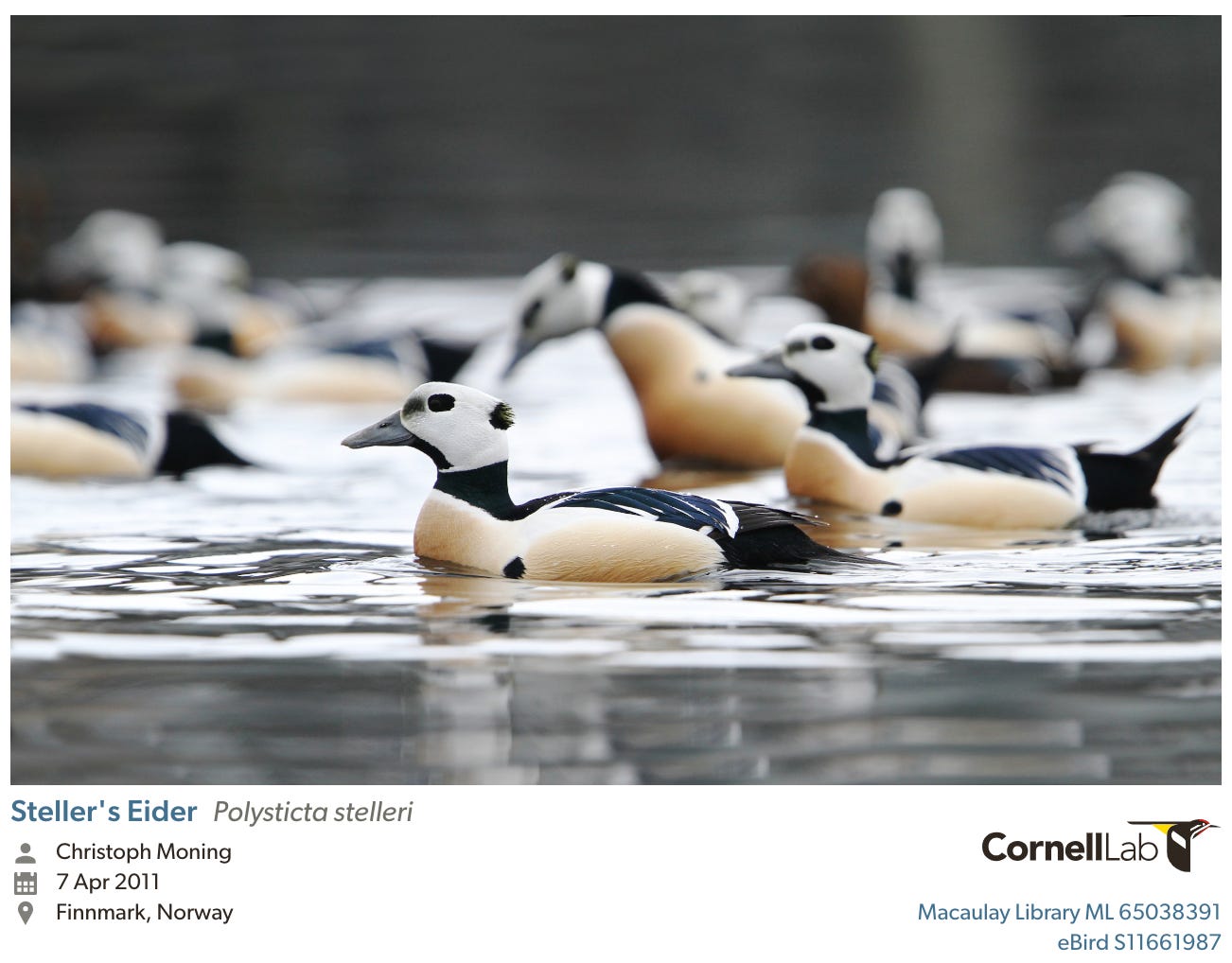

The Steller’s Eider, pictured at the top of the newsletter, was among the common birds around Disko Fjord. And as was common at the time, Fencker had shot the duck so he could collect it.

But the Governor lent perhaps the most insight into the Gyrfalcon, a fierce predator and the largest falcon in the world. The Gyrfalcon has a dark morph and a white morph. The white forms look like falcon-shaped Snowy Owls, especially so when they perch on the ground. The two varieties within one falcon species had to be a bit confusing to early naturalists. Think of the red morph of the Eastern Screech Owl and how much it differs from the gray morph. It would be tempting to think they were separate species. That’s about the situation with the Gyrfalcon. Wrote Kumlien:

In winter they subsist wholly on ptarmigans and hares. Governor Fencker, during his long residence in Northern Greenland, has had good opportunities for studying this bird, and he thinks there is but one species inhabiting the country, having known of instances where the parents of a nest represented the two extremes of plumage. Nor does the difference seem to be sexual, seasonal, or altogether dependent upon age.

In several instances, Fencker provided eggs to Kumlien and one wonders if in most cases he turned to the gun for assistance. King Eider, White-tailed Eagle, and Curlew Sandpiper were among the species whose eggs Kumlien added to his collection.

As for Kumlien’s birding on Disko, it was a dance between identifying birds that lived on Greenland and those that resided on Baffin Island. Kumlien was the first to find the Common Ringed Plover on Greenland, which previously only was known from Europe. The Semipalmated Plover, which many of us know in the Midwest, was rare in Greenland but more common on Baffin.

Of course, most birders know Kumlien in relation to a subspecies of the Iceland Gull that he was first to describe. The Kumlien’s Gull has white or pale gray wingtips which help to distinguish it from our local Ring-billed Gull. A few can be found on balmy Lake Michigan each winter.

The voyage to Greenland was meant to end in a rendezvous with the re-supply steamer to extend the expedition. However, the meet-up never happened so the Florence decided to head back to the United States.

Kumlien returned to Wisconsin, where he established a career as an ornithologist, much like his father. Ludwig Kumlien was a professor at the now-defunct Milton College before his passing in 1902. Howgate became infamous for embezzlement and a life on the run after his failed Greenland scheme. He apparently eluded capture for 13 years while using an alias and even working as a reporter for a time. He also had an uncanny resemblance to the actor Kevin Costner.

In a future piece, we’ll take a look at another remarkable Kumlien family member, Angela Kumlien Main. This one family, that I was unaware of until a few months ago, had a disproportionate impact on ornithology and is more than worthy of further study.

Note: This week’s piece and last week’s largely draw from Kumlien’s first-hand account in the Gerald F. Fitzgerald Collection of Polar Books, Maps, and Art, part of a broader core focus on Maps and Travel Narratives.

If you enjoyed today’s piece, you also might like this previous post from October 2024: