The evolution of field guides

Plus, a look at the new birding film, "Broken Flight."

A non-birding friend asked me a profound question recently: “How do you identify birds?”

I wasn’t sure what he meant at first, but I soon figured it out. What he was really asking was how to separate one species from another. Some people confuse a broad range of species, say robins and cardinals. But what he was referring to was ID’ing individual species, say within the family of sparrows, or within the family of thrushes. Separating a Lincoln’s Sparrow from a Savannah Sparrow, or a Swainson’s Thrush from a Gray-cheeked Thrush, can indeed be a challenge.

I wager most people operate at a higher level of birding, if at all. Discerning a robin from a cardinal, or a dove from a blue jay, may be a conundrum for many.

That got me thinking about some research I’ve been doing for the Winging It exhibition and The Best-Known Grouse of the Western States. I have a set of Alexander Wilson’s seminal four-volume American Ornithology (1808) sitting on my desk at work. It’s an amazing compilation with in-depth accounts of a wide variety of species. But it’s heavily technical and descriptive. Without any pictures, it wouldn’t have been a book that made bird identification very easy.

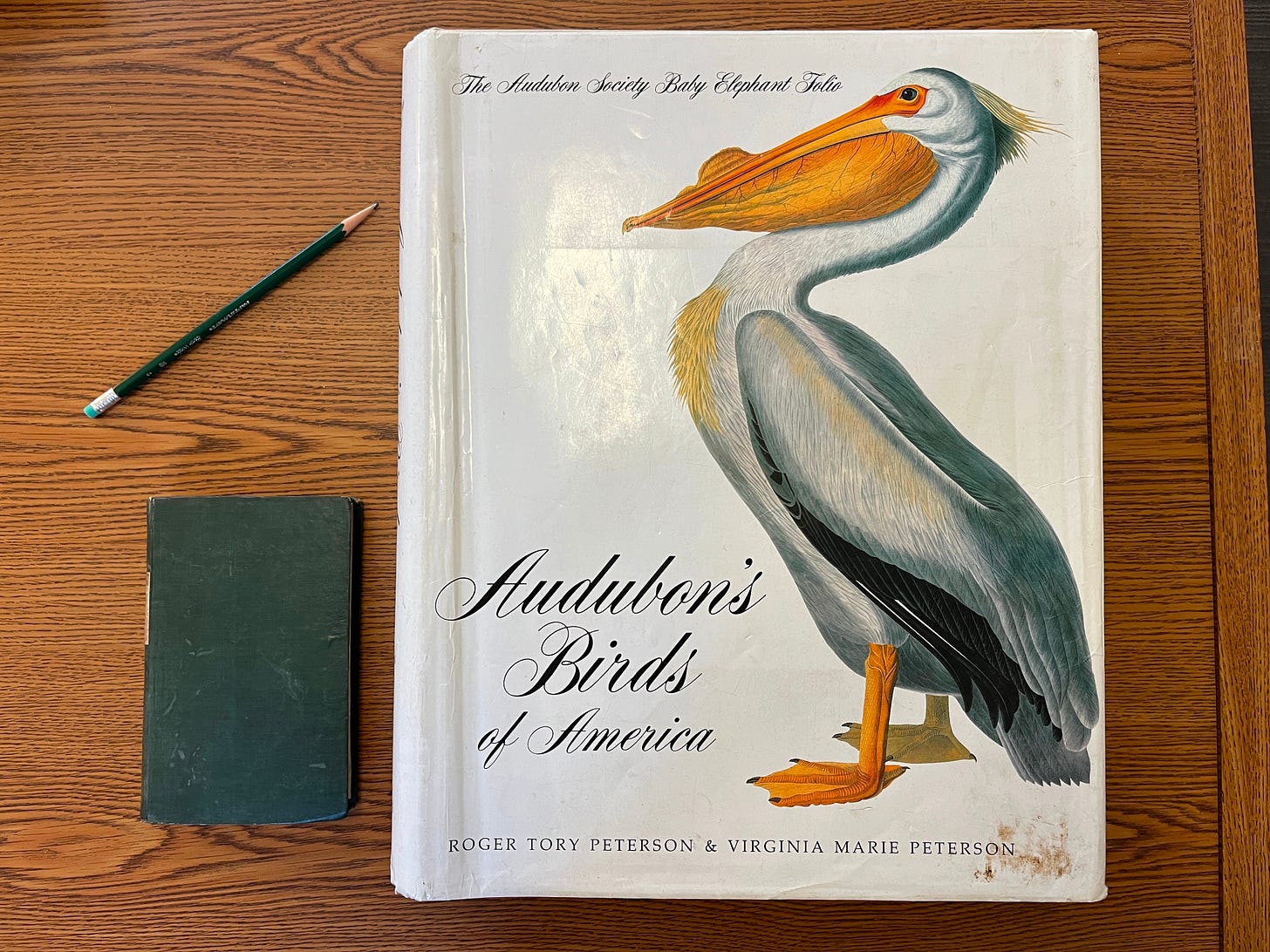

That’s where John James Audubon comes in. His illustrations gave people a glimpse of the birds discussed by Wilson and garnered even wider attention by placing birds in dramatic postures. But the portraits were huge and any bound volumes unwieldy, whereas Wilson’s books are very small. Someone on TikTok asked me if they may have been meant as pocket guides. But I don’t think so. Many of the birding tomes of the rest of the 19th century were text-heavy as well. There may have been a few with black-and-white engravings, but that was about it. Color printing was a sort of luxury.

Fast forward to 1905’s History of North American Birds, and a few color plates were appearing in more modest-sized books. Robert Ridgway, longtime Smithsonian curator and Illinois native, provided the illustrations.

Even then, the few plates in the book didn’t offer a whole lot of detail. In this case, they only depicted the head and upper parts of a few species. Further, the text was descriptive, but in a way only an ornithologist could understand. The focus was on study skins and obscure body measurements that had little use for people simply aiming to identify birds outdoors.

Enter Roger Tory Peterson (1908 - 1996), whose 1934 field guide was the first in the birding revolution. Peterson’s drawings included arrows pointing out field marks, the distinctive stripes, spots, patterns, and colors possessed by every bird. His simplified descriptions were understandable to a lay audience and a handy tool for experts as well. Of course, Peterson is synonymous with pocket guides that could easily be toted on most any birding outing.

Peterson as well as guides by Golden and National Geographic were the go-to books for amateur birders in the 20th century. But like everything, there is always another evolution in store, and the next one came from David Allen Sibley (1961 - ). Peterson guides lacked details on subspecies, juvenile plumage, and other variations. In his 2000 debut, Sibley packed all of those into the same-sized book while providing stunningly intricate depictions of feathering and coloration.

Now you might think that an essay written in 2024 about bird identification would conclude by saying the Merlin bird identification app made all these guides obsolete. But is that really true? There are details and descriptions that I refer to often in these guides—details that can’t be found via Merlin or All About Birds. Merlin requires a clear photo or clean audio. Further, I can look these birds up without an internet signal. I have their range maps and vocalizations all in one place. I can hold these works and experience them the way Peterson or Sibley intended. And last, Merlin still gets a lot of IDs wrong. The evolution of field guides laid the foundation for the identification tools we enjoy now.

Migration, interrupted

The new documentary short “Broken Flight” opens with scenes of a highly urban streetscape, all concrete and asphalt. It’s a bleak setting for a birding film, but that’s what “Broken Flight” is—a film about bird-to-building collisions and the people working to address the problem.

As noted in the film, downtown Chicago must feel something like another planet for birds migrating through the city from the North Woods. It’s timely that my viewing of the film came about one year after a deadly migration event that made international headlines.

Directors Erika Valenciana and Mitchell Wenkus follow bird collision volunteers as they make their morning rounds downtown. One volunteer, who’s helping out for the first time, watches as a bird strikes a glass window in real-time and plummets to the ground. “It actually makes me sad,” she says while taking solace in rescuing some of the birds that have hit buildings.

The birds that don’t make it past downtown are taken to the Field Museum of Natural History, where they are added to the body of scientific research. Studying bird dimensions over time can tell us a lot about climate change.

Birds that are injured or dazed are taken to a wildlife center in DuPage County, where they are examined and held until they can be re-released into the wild.

“Broken Flight,” an official selection of the Chicago International Film Festival, was beautifully filmed over several years, with close-ups of a wide variety of our most brilliant local species. The messages are that birds are a vital component of our ecosystem, that Chicago is a crossroads of migratory routes, and that people are helping and learning more about our populations. Birds would be much better off if everyone societally was aware of the stories told in “Broken Flight.”

“Broken Flight” will appear in the St. Louis International Film Festival next month. More information is available about the film here.

If you liked this post, you also might like these past posts:

Introducing "Winging It: A Brief History of Humanity's Relationship with Birds"

“We gave the natural science materials to the Crerar Library.”

Spring arrival dates for common birds

This February seems to be even drearier than usual. It may be because it’s one of the mildest in 150 years. Or that the lack of snow and ice—just 3.9% percent of the Great Lakes are frozen—is making this February even more muted.

As always, I enjoy reading each TWIB. Looking at the example of individual bird illustrations from the past I find it sad that all those birds were likely killed to achieve such detailed drawings. Last year I was visiting family in CA when my brother-in-law recited the headline of the estimated thousands of birds killed in Chicago during the 2023 Fall migration. I'd like to see the documentary - Broken Flight but I'm sure it would be a tear jerker for me.

You fast-forwarded right past 1899's Birds Through an Opera-Glass by Florence A. Merrian [Bailey], the godmother of modern birding! https://archive.org/details/birdsthroughoper00bailrich/mode/2up