Eider dreams: Ludwig Kumlien and Arctic birds

Part 1 of 2 chronicles a cold, dark winter on Baffin Island.

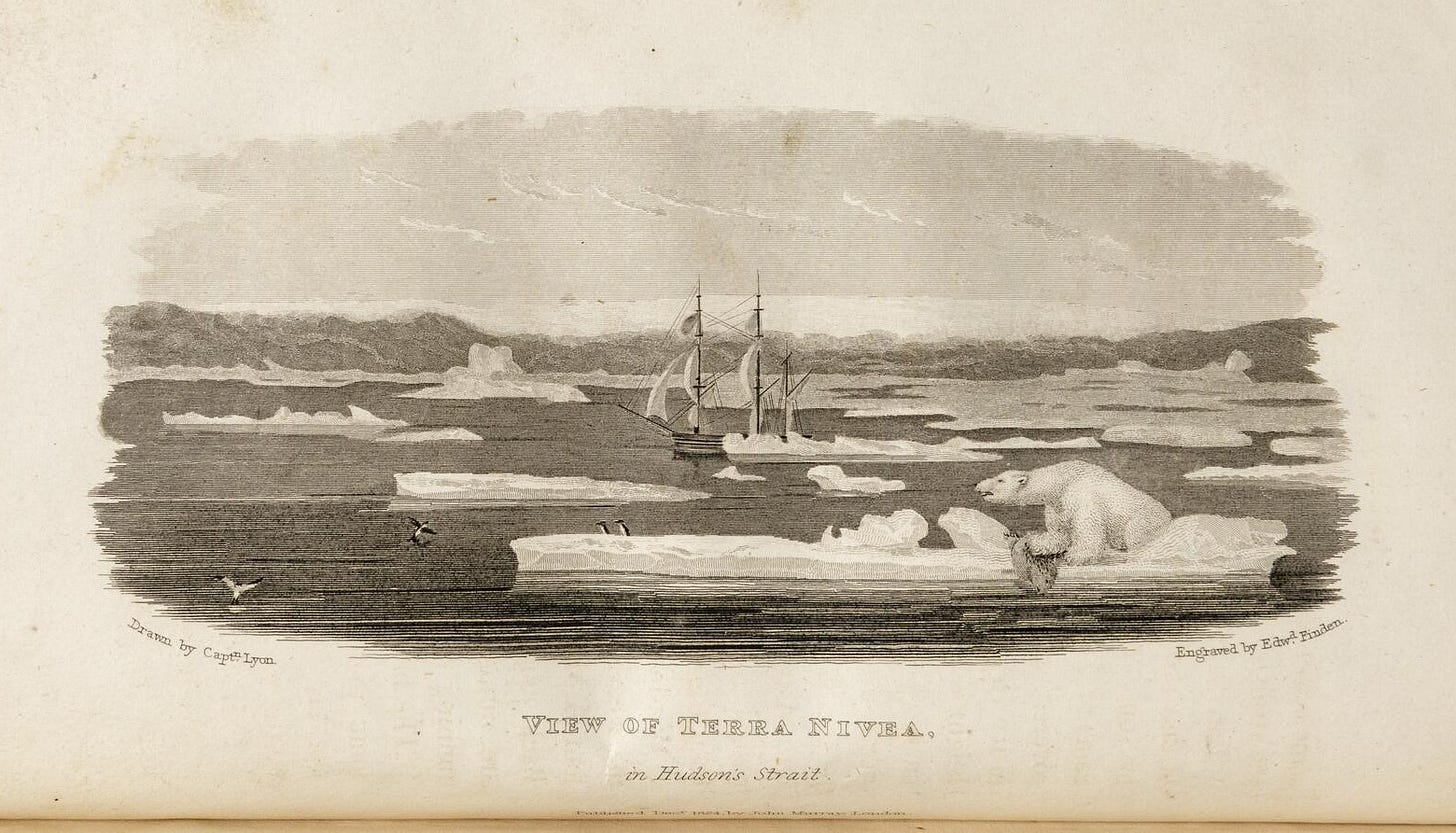

It’s hard for the twenty-first century mind to comprehend what life must have been like during the winter of 1877-78 on Canada’s Baffin Island. The Howgate Polar Expedition landed there in the fall after departing from New London, Connecticut. The goal of the U.S.-sponsored voyage was a mix of politics, trade, whaling, and to a lesser extent natural history. In truth, these goals amounted to colonialism, and it should be acknowledged that Arctic Canada was the domain of the Inuit people for centuries. (Note: there are quotes from a diary in this post that may now be considered offensive.)

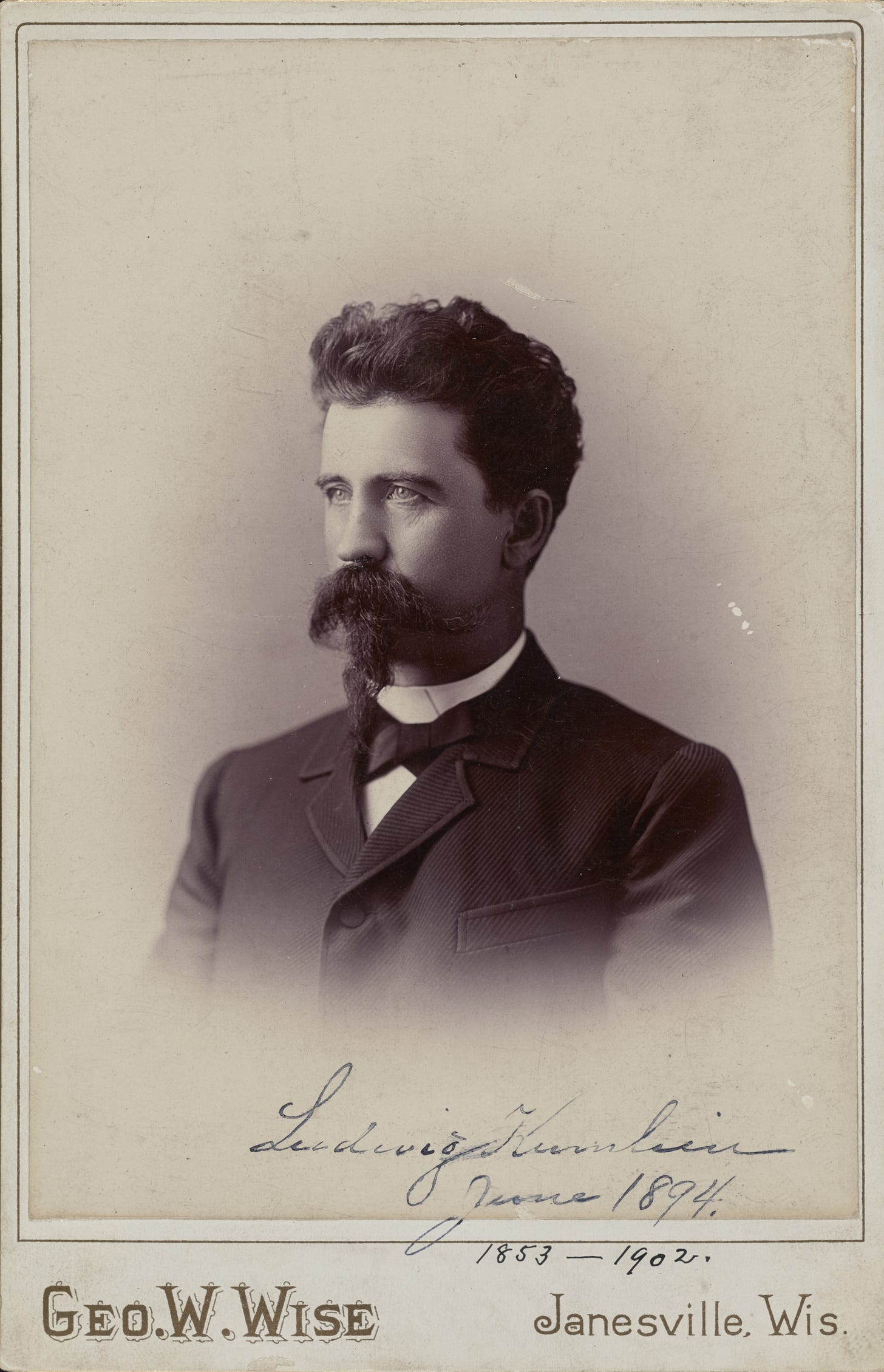

A young man named Ludwig Kumlien was one of the scientists on board. Kumlien was from southern Wisconsin, a little more than 100 miles from where I’m writing this newsletter. His father, Thure Kumlien, emigrated from Sweden in 1843 and became one of Wisconsin’s most noted naturalists.

Kumlien worked for the distinguished naturalist Spencer Baird and the US Fish Commission, around the Great Lakes and on the West Coast. He was hired to be the “representative of the Smithsonian Institution…for the purpose of collecting specimens of the flora and fauna of the country” on the expedition.

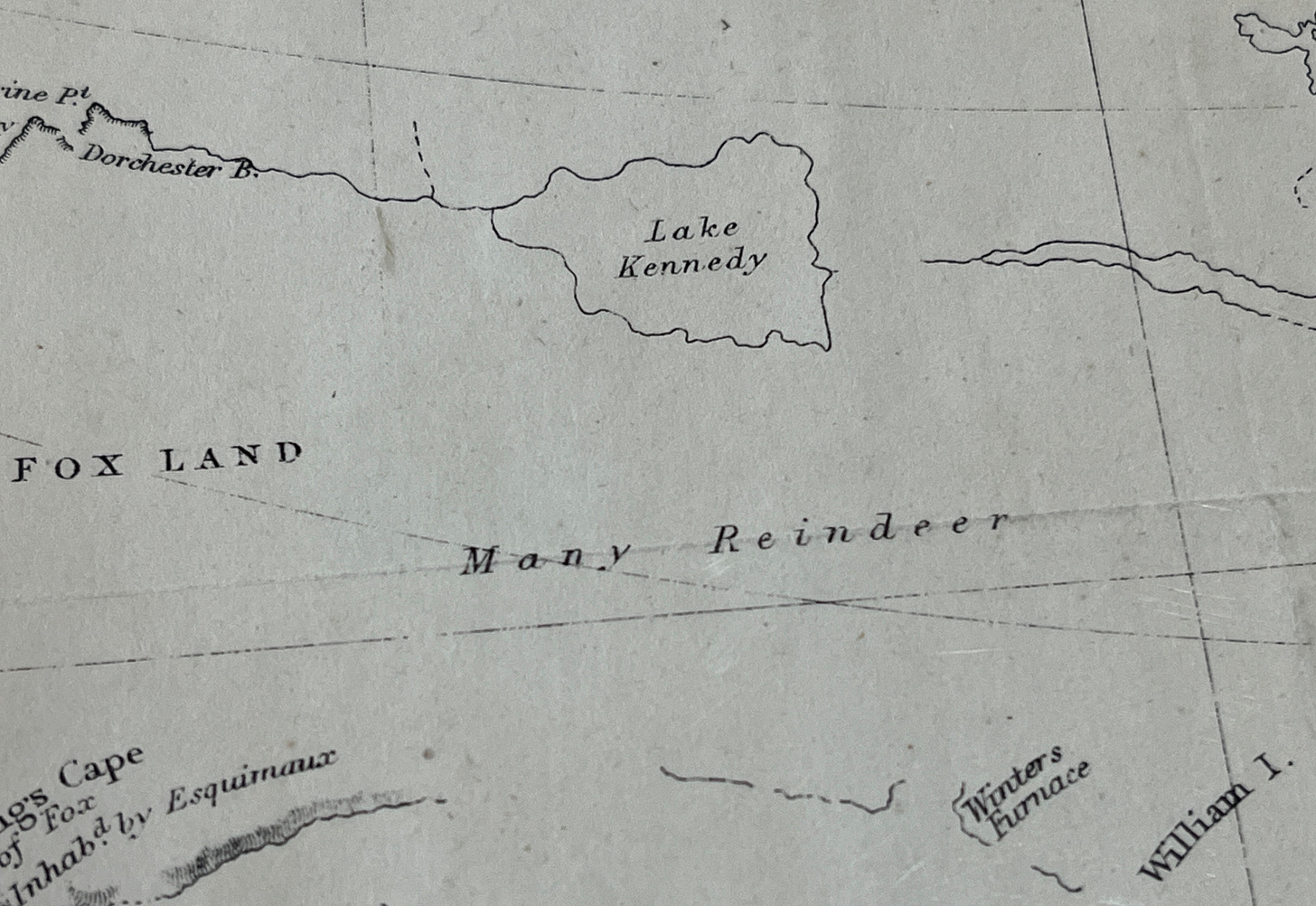

By early October, the vessel, the Florence, was hemmed in by ice for the winter north of the Arctic Circle. Kumlien relied on the local Inuit to build an ice hut in the form of snowy walls around a tent. As winter wore on, one can only imagine the conditions, with a limited food supply, darkness around the clock, and extreme cold. The scents of seal oil lamps, damp wool, and reindeer skin boots must have permeated the shelter. Kumlien spent most of his time gathering weather observations while on the lookout for “specimens” he could collect and bring back to the States in skeletal form.

The average temperatures from February 1 to March 19 were between 35 to 43 degrees below zero and the lowest temperature in February was 52.5 degrees below zero. Wisconsin winters were mild in comparison, and Kumlien wrote about enduring the seemingly endless cold and gloom.

“From our peculiar surroundings and the isolation to which we were necessarily subjected, we lost much of our wonted enthusiasm during the long-dreary winter, and found rest only in continual work.”

Further, Kumlien was limited as a naturalist by the geography of the basecamp at Cumberland Island, which was surrounded by impassable rocky shores for miles and miles. Kumlien’s greatest feat was the volume of insights into so much about Arctic wildlife in that winter, many insights the first by a Western naturalist.

“We improved every opportunity at this late day to secure specimens; but as the ice soon formed over the sound, our endeavors were far from satisfactory, especially as we were unable to procure a boat with any degree of certainty, as they had to be kept in readiness for whaling.”

It’s a wonder that Kumlien made as many sightings as he did. And certainly he was assisted by the Inuit, who introduced him to any number of species. Kumlien documented Inuit life as well as nature, recording dozens of bird species in their Native language. Some of Kumlien’s observations of the Inuit would be considered problematic in modern times.

Kumlien had to act quickly in the brief Arctic breeding season to describe species like the Common Eider (pictured at the very top of this post). He related an absurd observation of an eider incubating the wrong nest at a crowded colony.

“I have often lain behind a rock on their breeding islands and watched them for a long time. On one occasion we disturbed a large colony, and the ducks all left the nests. I sent my Eskimos away to another island, while I remained behind to see how the ducks would act when they returned. As soon as the boat was gone, they began to return to their nests, both males and females. It was very amusing to see a male alight beside a nest, and with a satisfied air settle himself down on the eggs, when suddenly a female would come to the same nest and inform him that he had made a mistake—it was not his nest. He started up, looked blankly around, discovered his mistake, and with an awkward and very ludicrous bow, accompanied with some suitable explanation, I suppose, he waddled off in search of his own home, where he found his faithful mate installed.”

After seeing the eider’s gaffe, Kumlien made his presence known, even after the birds thought all humans had left the island. It’s clear that the young man from Wisconsin had a sense of humor. When the eiders observed him, they were nonplussed.

“I could spare no more time to watch them, and crept out from my hiding place in full view of all, and a look of greater disgust and astonishment than these birds gave me is difficult to imagine; they evidently regarded such underhand work beneath the dignity of a human being, and probably rated me worse than a gull or a raven. So sudden and unexpected was my appearance that many did not leave their nests, but hissed and squeaked at me like geese; these same birds left their nests before when the boat was within a quarter of a mile of the island.”

Another anecdote demonstrates that conceptions of birds vary widely by culture. Take the American Pipit, an unassuming thrush-like bird that breeds in the far north. In the Midwest, people celebrate when they see one of these charmers during migration. To the local Inuit, the pipit is a messenger and interlocutor with reindeer.

“This little bird is considered a great enemy by the Eskimo. They say it warns the reindeer of the approach of the hunter, and, still worse, will tell the reindeer if it be a very good shot that is in pursuit, that they may redouble their efforts to escape. The Eskimo never lose an opportunity to kill one of these birds. I have seen one with a rifle wasting his last balls in vain attempts to kill one when he knew that there was a herd of reindeer not more than a quarter of a mile away.”

When the ice finally broke up, Kumlien would shine a light on two species that resonate with us today in the Midwest. That would take place on Greenland, on the other side of the Davis Strait from Baffin Island.

To be continued in a future installment.

One year since we lost Flaco

Flaco died almost exactly one year ago today. The Eurasian Eagle-Owl delighted many by surviving in Manhattan after escaping from a zoo enclosure. Now there’s an art and photography book by Jonathan Hollingsworth that chronicles Flaco’s extraordinary story. Included in the book is a Flaco collage by our good friend Tony Fitzpatrick. You can pre-order the book here. (Note this is one of two recent Flaco books, there’s another called Finding Flaco.)

Thanks to all who’ve taken the step to become a paid subscriber. If you’d like to show your support for this newsletter, click the button above. The vast majority of subscribers receive this newsletter for free because of your support.

Fun read!