Humans at loggerheads with an endangered species (yet again)

Thanks to Hoosiers, a tiny sliver of hope for shrikes in the Midwest. Spoiler alert: Habitat is again the answer.

Check out this quote from a Midwestern natural history account, about the development of a prairie. Would you say this was from 2023, 1983 or 1883?

“Instead of an absolutely open prairie some six miles broad by ten in extreme length, covered with its original characteristic vegetation, there remained only 160 acres not under fence. With this insignificant exception, the entire area was covered by thriving farms, with their neat cottages, capacious barns, fields of corn and wheat, and even extensive orchards of peach and apple trees…As a consequence we searched in vain for the characteristic prairie birds.”

Hard to tell, right? The desire to convert prairie to farmland or other forms of human encroachment very much persists to this day.

The answer to the original question? 1883. Robert Ridgeway began tracing the ornithology of Illinois from his home in the Mount Carmel area in 1871. Even as he was dismayed, his description of small-scale farms sounds downright idyllic by our 21st century standards. If only we still had orchards and fence rows to separate our properties and create important edge habitat for species like the American Kestrel and Loggerhead Shrike.

Speaking of which, Loggerhead Shrikes are state endangered in Illinois and nearby Indiana. In the Hoosier State, they’re down to only a handful of pairs, the habitat devastation has been so great. Most are about an hour’s drive from where Ridgeway grew up. He writes in his seminal “Ornithology of Illinois” that he often found shrike nests in apple trees, which seemed surprising.

My knowledge of shrikes stems from Indiana’s Shrubs for Shrikes program, which encourages folks to “adopt” a shrike so that the Department of Natural Resources can work with private land owners to plant red cedars to replace all those lost fencerows from Ridgeway’s era.

“Loggerhead shrikes often choose dense bushes and trees to build their nests in,” says Amy Kearns, Assistant Ornithologist, Indiana Department of Natural Resources. “I’ve seen several nests in Bradford (Callery) pears, which have a dense branching structure similar to some apple trees. I’ve also noticed that shrikes in southern Indiana seem to prefer nesting in linear structures, most commonly in fence rows, but also in trees planted in a row along a driveway or road. One year I saw them nest in a pear tree that was in a backyard orchard. I also know that in Ontario1, shrikes prefer to nest in hawthorn trees. Hawthorns, pears, and apples are all in the same genus so it is easy for me to imagine Ridgeway’s account of shrike nests in apple trees.”

Shrubs for Shrikes appears to be working, according to the latest update from Kearns:

So far, 70 bushes have been planted and shrikes frequently use these cedars for cover and hunting perches. During 2023, two broods of shrikes were seen taking cover in these planted cedars, keeping them safe from predators like hawks. We expect that the bushes will continue to help shrikes in the coming years.

Indiana shrikes had a great year in 2023! They raised 31 young, which is well above typical years. We found 8 nesting pairs, 5 of which were in Orange County, and 1 pair each in Daviess, Spencer, and Washington Counties. Forty-one shrikes were marked with color bands around their legs, so if they return to Indiana to nest or are found in another state, we will be able to recognize them.

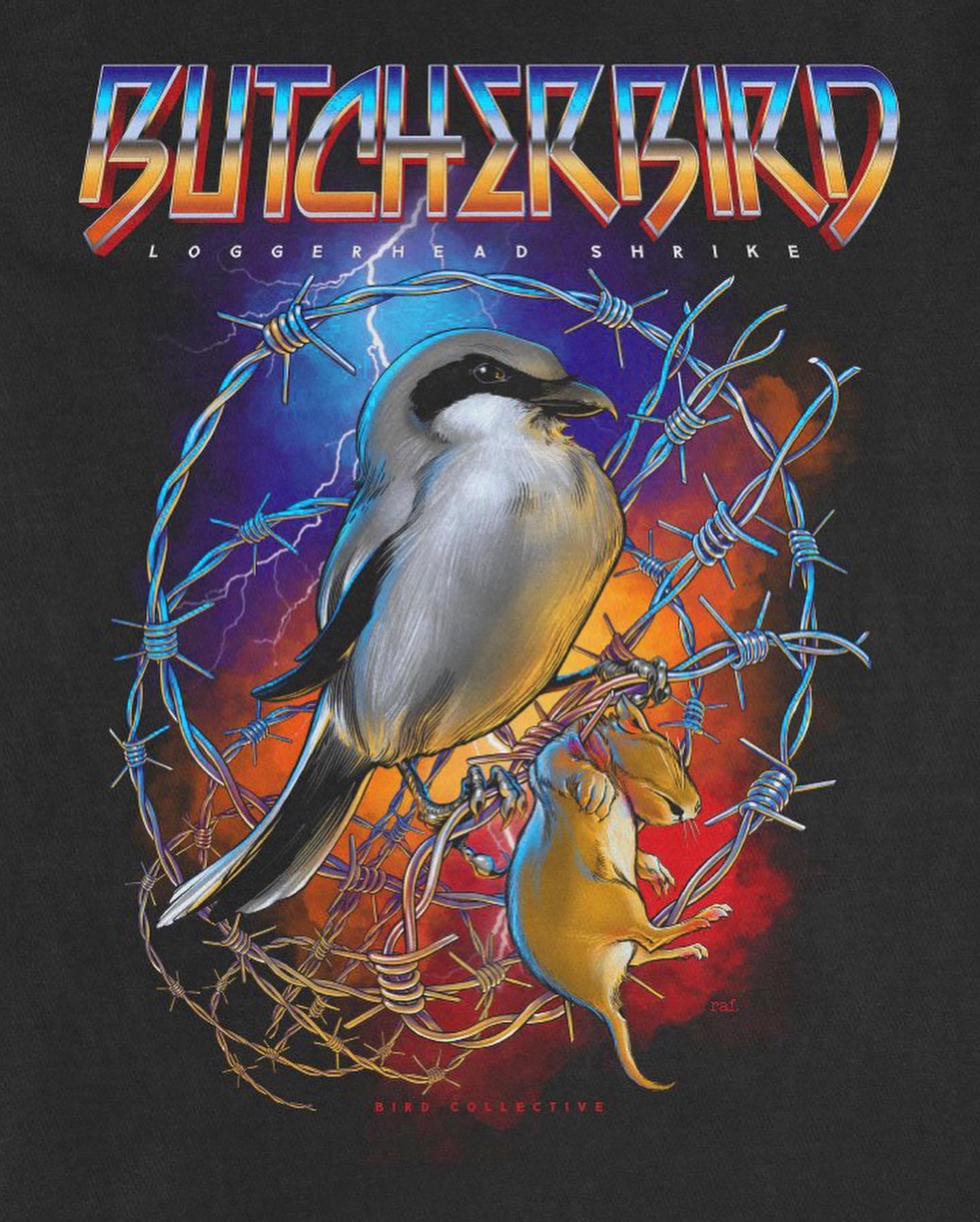

Loggerhead Shrikes, which remain much more populous in the southern United States, are a songbird predator that uses its disproportionately powerful, hooked bill to catch and transport its prey. The robin-sized birds then impale and cache prey items like arthropods, reptiles, mammals, and birds on thorns or barbed wire.

In 2021, I wrote about adopting a shrike, and although mine was never recaptured the spirit of the program continues and is inspiring. There’s a satisfaction in helping shrikes thrive but also in returning the landscape to resemble something more sustainable. Indiana DNR reports that more than 40 shrikes were color-banded during 2023 and that they are now available for adoption.

Orange Co 2491-00940 LG/WH, SI/DB SY M, affectionately known as our “old man shrike,” is 7 years old this year and the oldest banded shrike ever observed in Indiana.

He was last seen during January 2024, and a month later a young male shrike was occupying his territory. Does this mean he is no longer with us, or could he have been pushed to a nearby farm? We are hoping that he’ll turn up soon and nest again this spring.

(Content warning: a deceased bird is described)

The development Ridgeway lamented is a far cry to what birds face today—including many deadly human-involved risks. Take Daviess Co 2491-09443 DB/OR, SI/OR HY M, a 3-year-old bird that was half of the only known pair of nesting shrikes in Daviess County last year. After fledging five young, he tragically was found dead in the road during July, with vehicle collision as the likely cause of death.

This is the same fate that his father suffered in 2020 and is likely related to the huge increase in human population and development in this area of Daviess County during recent years.

Adopting a shrike is a tangible step that makes a difference for a very unique species. We can take solace when these sad stories arrive but also strive to take action on our own. The endangered bird in your area may not be a shrike; there are species all around us that need more habitat and protection from development. It’s not just assisting a specific bird, it’s about returning the landscape to a modicum of what it was generations ago.

Having driven through Ontario recently, I understand why they have shrikes on their farmland and we don’t. It’s (relatively) small scale farming, laden with trees and wind breaks, a patchwork of farmland and forest. That just doesn’t exist in the Midwestern US.

Loggerhead shrikes and The Bird Collective are a good combination. I have a heavy metal themed Kingfisher shirt from the TBC that is amazing. The Savanna Institute and Canopy Farm Management are hard at work planting trees and shrubs on Midwestern Farms as part of our mission to expand agroforestry. Hopefully, all those shrubs will also help the shrikes.