Bird bounty laws were indeed destructive

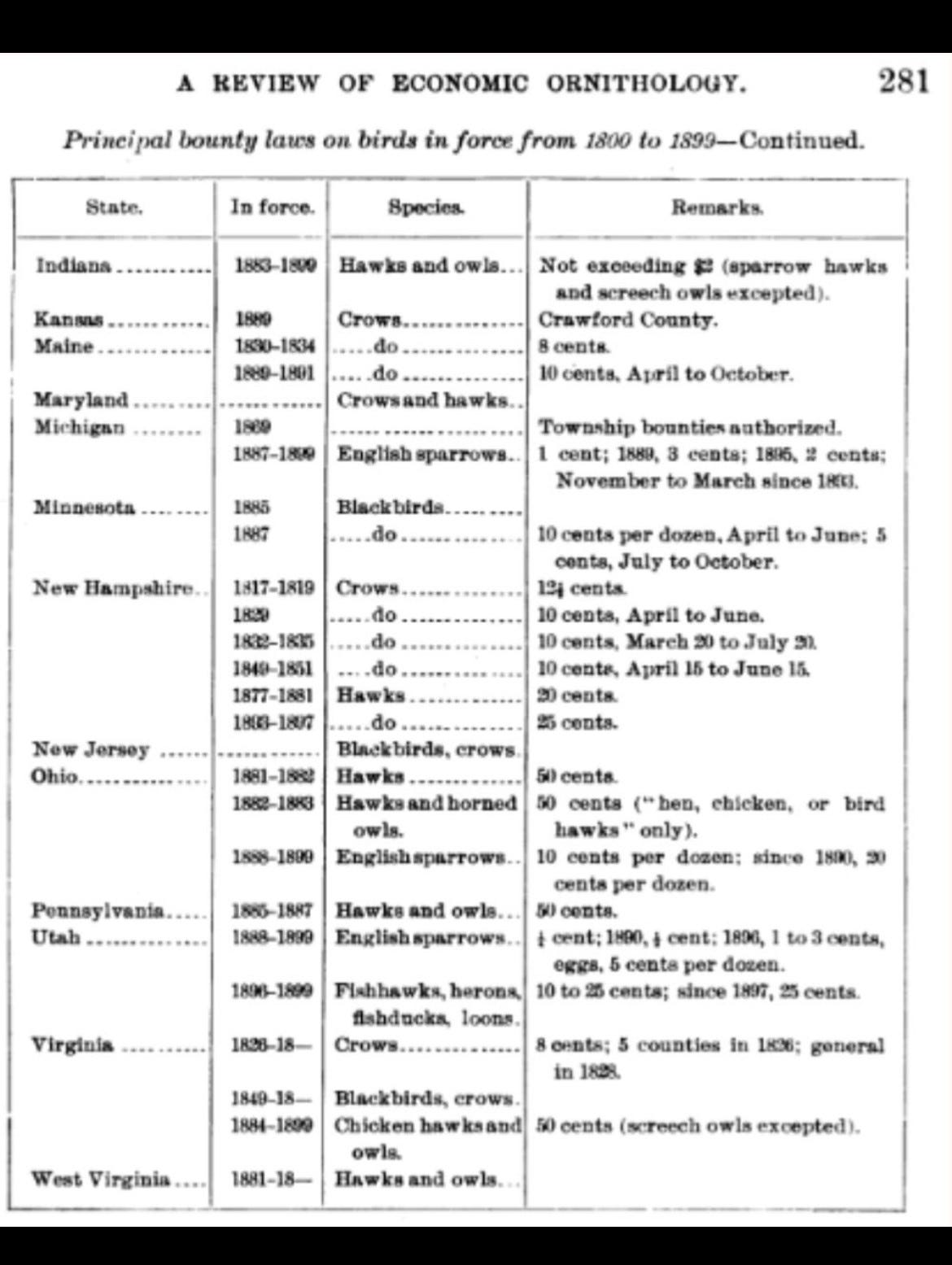

In 1899, a government report chronicled at least 16 states that reimbursed people for killing crows, blackbirds, and sparrows.

The bird bounty laws of the late 19th century were perhaps the nadir of human-bird interaction in American history. Birds always had been gunned by settlers, first for subsistence and then for selling at markets in major cities. Menus in urban areas were laden with plovers, sandpipers, swans, ducks, turkeys, pigeons, and grouse by the 1890s.

It was an era when birds were assessed for their economic value. The reality was that corvids, raptors, and smaller songbirds weren’t as desirable as more traditional game. In fact, they were actively seen as a problem to be eliminated—raptors because they consumed livestock and corvids and songbirds because they consumed crops.

T.S. Palmer, Assistant Chief of Biological Survey, under James Wilson, the Secretary of Agriculture in the McKinley Administration, gestured toward the harm of these practices in an 1899 article. It was a time when the modern conservation movement had yet to take hold.

Palmer wrote in the Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture, in a “Review of Economic Ornithology” article and a section appropriately titled “Measures for the Destruction of Birds—Bounty Laws.” Palmer stated:

“Efforts have been made since colonial days to exterminate certain birds considered injurious to agriculture. The early settlers, seeing their crops attacked by crows, blackbirds, and ricebirds1, undertook measures for bird destruction long before they thought of bird protection.”

These laws existed in only a handful of states by the turn of the century. Soon they would be superseded by laws that protected birds, though it took the extinction of the Carolina Parakeet and Passenger Pigeon to get there. The decimation of wading birds for plumes was another seminal event that led to the establishment of the first wildlife refuges. And the field of economic ornithology mercifully began to wane by World War II.2

As I researched economic ornithology for the bird-focused exhibition I’m working on3 I thought about how this dreadful concept might relate to today. Of course ricebirds, or Bobolinks, have long since been highly threatened and become very uncommon. Bobolinks were a once prominent feature of our avifauna going back centuries and are now confined to small grasslands in a handful of locales on the continent. One has to think all the shooting back in the 19th century—as well as later land development—left its mark on the species’ populations. The settlers just couldn’t stand for the Bobolinks’ love of rice.

It’s easy to think that economic ornithology is a relic of the past. However, there are echoes in contemporary efforts like environmental mitigation, which attempts to assign monetary value to ecosystems lost to development. (I wrote about this in a post in April 2023.)

To say the least, the intrinsic value of nature often gets lost in the chase for the almighty dollar. Not everything needs to be quantified in our numbers-obsessed society. Rather, the natural world should be appreciated for it is—irreplaceable.

Local documentary features Bird Collision Monitors

“Broken Flight” is a documentary short that follows the Chicago Bird Collision Monitors, a volunteer group that rescues and records birds after they collide with skyscrapers, will make its Chicago debut as part of the Chicago International Film Festival. The film has had a wonderful reception, with festival acceptances across the country — from DC to Boise, Telluride, Philadelphia, and Marquette, Michigan. Congratulations to filmmakers Erika Valenciana and Mitchell Wenkus, and I’m proud to say I was a community consultant on the film. “Broken Flight” will be shown on October 18 and October 23 as part of the festival. Erika will be joined by Annette Prince on the 18th and Mitch will be on hand on the 23rd.

The birds we now know as Bobolinks were known as ricebirds or reedbirds throughout the 19th century.

The Bird History Substack has a nice summary of economic ornithology, from earlier this year.

Our Bobolink (and Short-eared Owl, etc) habitat is being not so slowly consumed by commercial interests. Amazon campus. GE campus. On and on it goes. Irreplaceable.

The gov't. really should still offer a bounty for English House Sparrows and add one for English Starlings.