What technology has done to field identification

The future of birding isn't bleak at all.

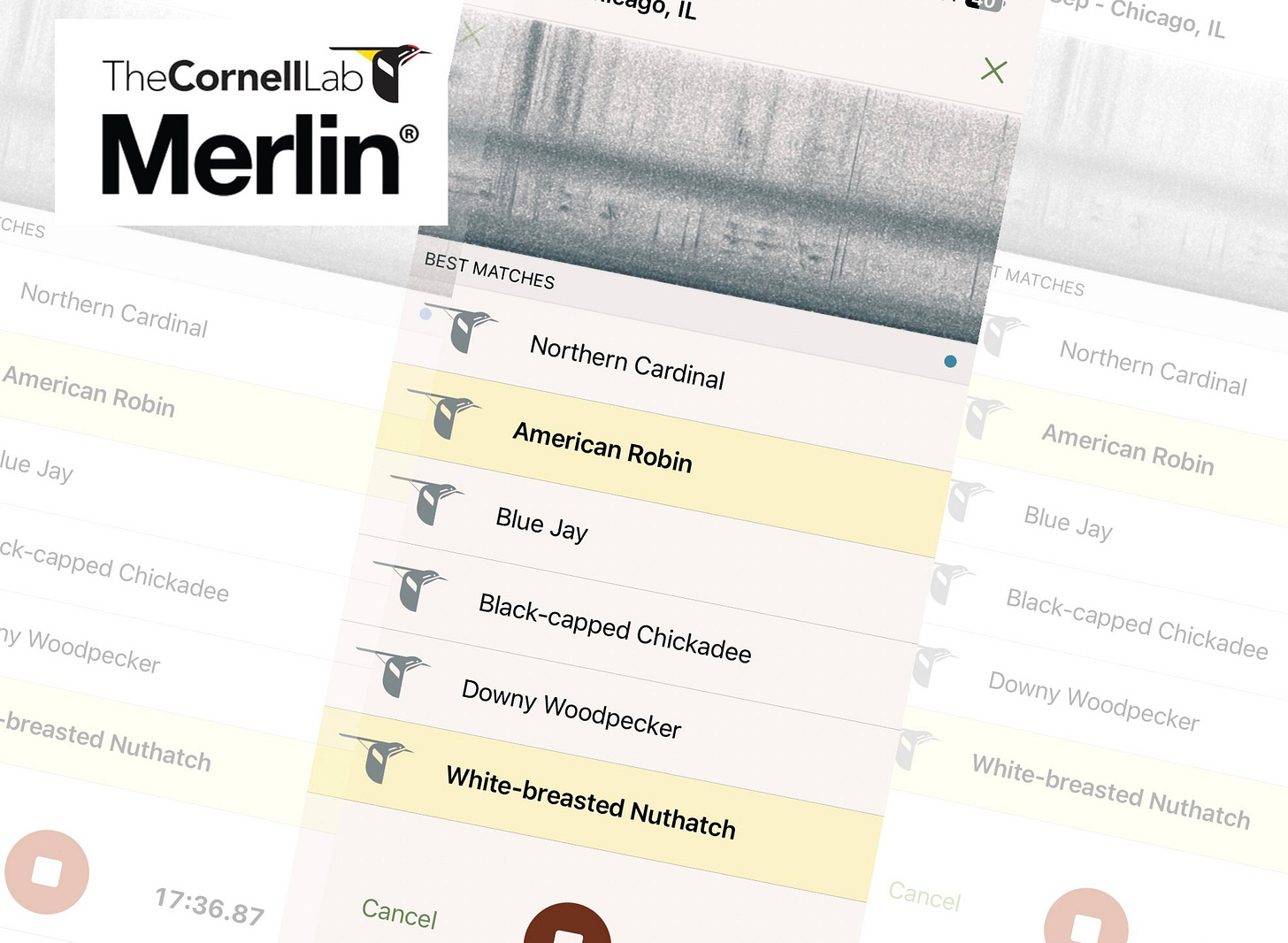

A stray thought has occasionally crept in as I’ve increasingly used the Merlin app to identify and verify bird songs. That is, “what was I doing all those years memorizing bird songs and puzzling over identification challenges?” I’ve wondered if the bird identification skills I honed before Merlin—which I only began using in recent years—had become less important, or at least less valuable. (If you’re not familiar with Merlin, it can identify birds to species through photos and audio.)

Pete Dunne, founder of the World Series of Birding and a Cape May legend, posed a question along these lines, “Is Field ID Dead?” in the July issue of Birding.

Dunne also goes further back and points out that digital photography itself opened up new frontiers in field identification, using the maddening Empidonax flycatchers as examples. But digital photography, while certainly innovative, feels like a lot less of a sea change in field identification. One still has to sync up a camera to a computer or phone to start parsing a sighting or an ID.

Dunne captures the essence of Merlin’s vast impact here:

The Merlin Bird ID app has brought field identification into a new facilitated era that sidesteps the hunting apprenticeship stage of becoming a birder the way many of us define it: a person devotes time and focus required to gain identification skills. It is no longer necessary to indenture your life to learning bird vocalizations. With Merlin, a nine-year-old kid down the street can identify spring warblers by their song with greater accuracy than I who have dedicated 65 years to this endeavor.

I think advances in bird identification technology will mostly affect—and hopefully facilitate—the apprenticeship stage of bird study: that initial internship and sometimes frustrating stage when new birders are just learning their birds.

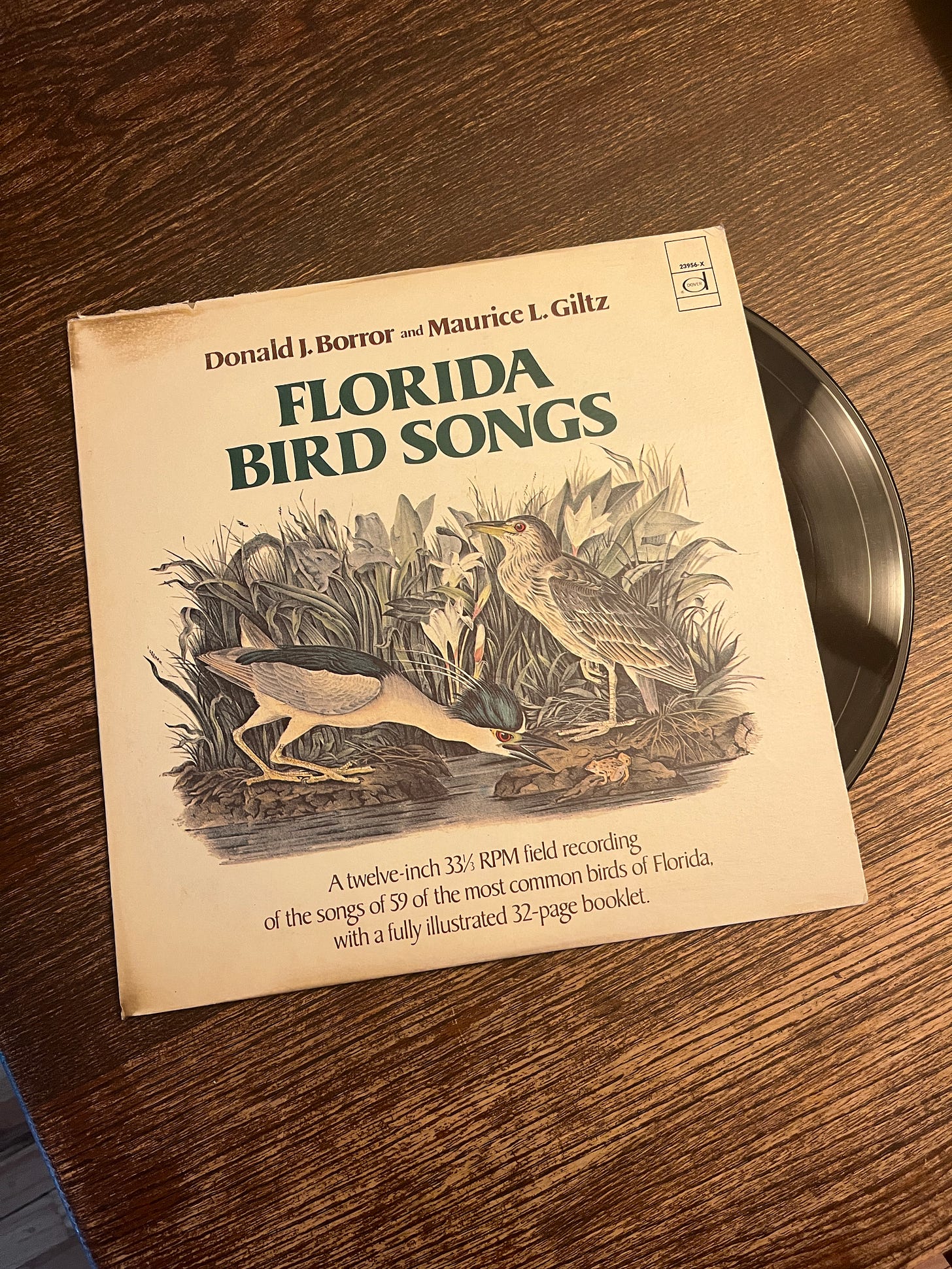

Indeed, I read Dunne’s essay the same day I nabbed a bird song record, a vinyl record, at a garage sale. Learning these songs required sitting next to a record player for hours. At least with a cassette, I could listen to the songs through my car stereo.

The truth is, one can still sit with a record, cassette, or CD, or bop around All About Birds or Xeno Canto to learn bird songs. That’s part of the fun. Cue up the bird songs on a cold late March day and get ready for migration.

Dunne writes:

As for me, next spring I’ll go out and relearn warbler songs, just as I do every year. Greater challenge equals greater achievement equals greater satisfaction.

I appreciate this thought. At least for me, my phone also will still be listening for birds on most outings. Used judiciously, Merlin is too valuable of a tool. There are warbler call notes that I’d absolutely be unlikely to pick out on my own.

The truth is, birding’s been evolving since the time of the first telescopes and binoculars, and probably before that, too. Making bird ID easier is something that can bring more people into this pursuit. And that’s almost always a good thing.

After finishing the above piece, I went birding in a local forest preserve on Saturday. That’s when I had a field identification experience that seemed to confirm that Merlin hasn’t completely altered the fabric of birding. There were quite a few raucous Blue Jays around (when aren’t they raucous), and they were making all sorts of calls as jays are wont to do. But there was another call—another species—mixed in. I had Merlin open and listening for birds, but it wasn’t picking up anything other than the Blue Jays. The call was something like a hoarse Red-bellied Woodpecker, which led me to conclude that I was hearing a Red-headed Woodpecker, an uncommon and delightful species in my neighborhood. I checked Merlin again, and it had nothing. Now, there were a few factors at play. The woodpecker was quite distant, so it’s possible it wasn’t in range of my phone and Merlin. The Blue Jays were indeed loud, and there were planes on the approach to O’Hare. But still, it took knowing Red-headed Woodpecker calls and experience with the species and this location to identify the bird. And when I lifted my binoculars toward a big dead tree in the distance, there was indeed a Red-headed Woodpecker at the very top.

Celebrating Chicago Ornithological Society

Chicago Ornithological Society brought back its annual fundraiser after a four-year hiatus on the evening of Aug 26. The festivities included a big turnout and an exciting venue in Metropolitan Brewing, overlooking the North Branch of the Chicago River.

Check out COS’ new logo, featuring a quintessential Chicago bird, the American Woodcock. COS has a lengthy and fun piece about its new logo and its past logos—both also woodcocks—which date all the way back to Dr. William Beecher. Eagle-eyed TWiB readers may know that Beecher was the legendary director of the Chicago Academy of Sciences and receives a shout-out in the “Monty and Rose” films.

If you liked this post, you also might like:

Press the like button below if you enjoyed this post, or leave a comment!