The earth is an exquisitely balanced system composed of complex and elegant threads of connection. As these threads fray and unravel, species decline and disappear. Our way of being in the world is akin to “a bull in a china shop,” and we do not even fully appreciate what we are destroying.

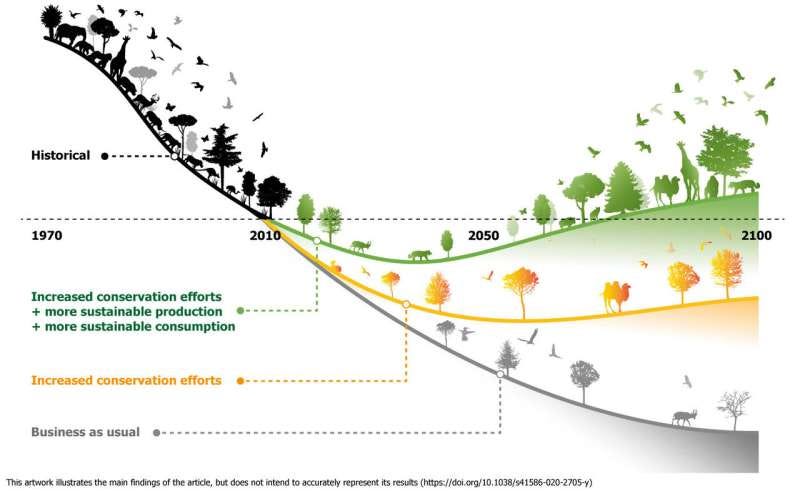

Scientists appreciate the threats that we face and the need to restore biodiversity. Recent studies have outlined the need to bend the curve of biodiversity loss. This requires that we change our way of being in the world. We have taken too much and it is in our best interest to start giving back, to make space for more life.

This may seem like a small step, but one of the most important ways you can give back and support viable populations of birds and other wildlife is to landscape your yard with native plants. This trend is discussed in Douglas Tallamy’s 2020 book, Nature’s Best Hope. He outlines a plan to create a Homegrown National Park movement that focuses on the 40 million acres of land devoted to lawns in the United States.

Ninety percent of our lawns are currently covered by exotic turfgrass. There is not a single species of wildlife that can complete its life cycle in a lawn.

Tallamy believes this approach is good for people, wildlife, and nature.

“I am promoting actions that create immediate short-term gains for people. Such actions will also deliver long-term ecological benefits landscaping will no longer degrade local ecosystems. It will become synonymous with restoration. We will not be living with less we will be enriching our lives with more pollination services, more free pest control, more carbon-sequestered soil, and rainwater, held on our land, more bluebirds in our yards more monarchs sipping nectar from our flowers, more species of all kinds, increasing the stability and productivity of our ecosystems. This approach to earth stewardship will no longer be the unfulfilled dream of a few environmentalists, but a culturally embraced imperative not only because we have no other choice but because it works. It is nature and humanity’s best hope.”

In order to help more people embrace the new trend of landscaping with native plants we have to grapple with convenience. Convenience rules our lives. It is one of the most powerful forces shaping individuals and economies. Streaming TV, Amazon, cell phones, and Google are irresistible for most people. While there are undeniable benefits to these modern technologies, they also have a dark side in disconnecting us from the natural world.

Engaging and deeply meaningful tasks, like gardening and landscaping, that were once more common, slowly fade away under the power of distraction and convenience. We lose a little of our humanity as the activities that foster connection and well-being disappear. This leaves a hole in our lives that convenience cannot fill. Hence, the longing that people have for a connection to each other and to nature. This biophilia runs deep and is a powerful force.

Combining convenience and biophilia can help a broad and diverse cross-section of the U.S. population change how they think of their yards. For most people, conservation begins in their yards. One-third of the U.S. population, or 86 million people, enjoy watching wildlife. Eighty-one million people watch wildlife within one mile of their homes. Bird feeders are the primary form of wildlife watching, and most birdwatchers are novices and can identify 10 or fewer species.

This core group of existing birdwatchers are logical early adopters who can enhance their birdwatching by adding native plants, and water features, keeping cats indoors, and ensuring bird window strikes are minimized to make their yards a sanctuary. As more people join the movement, each yard will become a link in an interconnected network of yards that form corridors of habitat that allow animals to travel from yard to yard. This helps their populations expand and adapt to shifting conditions.

If the network becomes large enough, wildlife can begin to recover and we can reverse the population declines that so many species are experiencing.

Thus, a significant opportunity lies in making it easy for urban residents to engage with nature and birds. Parks and refuges in cities and on the urban fringe that combine diverse native vegetation and infrastructure for wildlife observation are crucial for supporting a new land ethic. By tapping into people’s desire for connection with nature, we can increase the level of skill and commitment people have to observe wildlife. This will help them move from a casual to a more serious level of wildlife viewing, which would create more constituents willing to become engaged citizens and supporters of a modern conservation movement. I’ve seen what’s possible in my own community with a movement to identify and protect the shallow wetlands known as fluddles.

Once people are more interested in traveling to see birds and other wildlife, the challenge becomes helping urban residents feel comfortable in rural areas. Many of these rural natural areas are hard to find, and once visitors arrive, little is visible to make them feel invited into the space. This is particularly true for women and underrepresented populations. But small shifts in intention and focus can make new visitors feel welcome.

This includes good signage with images of people who look like them and information on apps that aid in plant and wildlife identification like iNaturalist, Merlin, and eBird. Short, clearly marked trails that lead to good locations for observing wildlife are critical. Strategically placed, purpose-built blinds designed to provide close encounters with undisturbed birds are another key piece of infrastructure. A group of birds foraging in the middle of wetlands hundreds of yards away is only so interesting for new birders. That same group of birds foraging 20 yards away can capture the viewer’s imagination.

Up-close encounters with birds and other wildlife will create future conservationists. A big, mixed flock of waterbirds foraging at close range in a healthy wetland full of native plants can compete with YouTube. Mix in some Trumpeter Swans and Sandhill Cranes, and people may abandon watching a football game. Videos of the waterbirds will end up on social media. This is free advertising and an effective means of recruiting more wildlife observers. Positive feedback loops will take hold. More people will start to visit. Visitors will become more connected to the land and birds, and they will be willing to travel even farther to see the spectacular abundance on display in larger natural areas. This also opens up nature-based tourism benefits for small, rural communities nearby.

Government agencies like the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) are starting to adapt to this new era. One contribution birdwatchers can make is to help the IDNR appreciate the extent to which cultural diversity supports biodiversity. We need people from marginalized groups and those with novel perspectives to be centered and appreciated. We need to create space for new ideas and take those ideas seriously. Recruiting and mentoring people with diverse perspectives is key. This will allow the conservation movement to tap into new talent, sources of money, and the skills and energy required to restore and manage a large-scale interconnected network of natural areas capable of maintaining biodiversity.

Within this new landscape, nimble environmental nonprofits, urban planners, parks departments, and the new Homegrown National Park movement are poised to deliver new power to the conservation movement.

Embracing this new power increases the value of restored natural areas in and near urban centers. These refuges for birds and people are the nexus for resilient, place-based conservation. As people explore these areas and learn to slow down, observe, and connect, conservation will blossom.

Bill Davison is an award-winning wildlife photographer, biologist, farmer, and agroforester, on a joyful journey to share his love of nature with others. You can follow him on Substack via

:Watch the trailer for FLUDDLES

Earlier this month, we released the trailer for the new documentary, FLUDDLES, about the birds of Illinois wetlands. Sometimes simply described as “big puddles,” fluddles appear in the spring and fall and provide habitat and forage for a diversity of waterfowl and shorebird species. FLUDDLES takes viewers on a journey to these secret, oft-fleeting wildernesses in a time when Illinois has lost 90% of its original wetlands. FLUDDLES features those who enjoy the beauty of wetlands while showcasing the movement under way to construct more wetlands, which provide critical habitat, reduce flooding and erosion, and help to ensure healthier waterways.

FLUDDLES is a follow-up to THE MAGIC STUMP and the second in Turnstone Strategies’ Prairie State film series.

If you enjoyed this post, you also might like…

So much of this week's essay is powerful. I am struggling with where we live because it has an HOA that requires lawns. So we either move or try to change the rules, which I doubt will happen. I grew up in the SF Bay Area and we used to see tiny houses near Candlestick Park that had concrete instead of front lawns. Some were even painted green. We thought this was hysterically funny. At least the concrete didn't need watering. I am going to print this week's article out and quote it when I can.