The real James Bond was a legendary birder

A Q&A with Bond biographer Jim Wright.

If you hang around Caribbean birding folks long enough, someone will mention Jim Bond. That’s because Jim, or more formally James, was the pre-eminent ornithologist of the Caribbean in the 20th century. His Birds of the West Indies was as necessary as binoculars and a tube of sunscreen when visiting the islands.

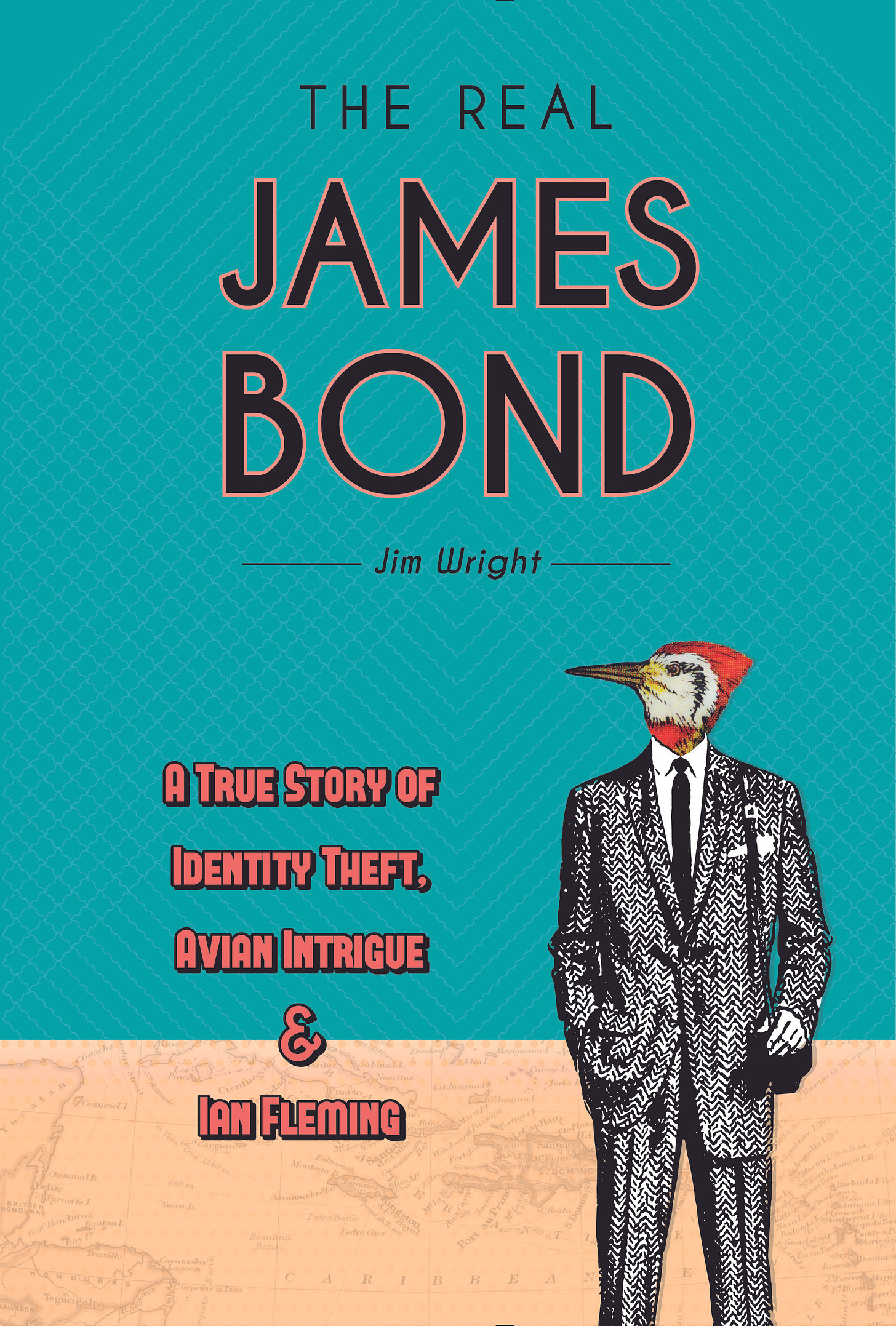

It’s taken me some time to get around to it—more than I’d like to admit—but I finally read Jim Wright’s book about Bond, who somehow became the namesake for Ian Fleming’s legendary character and whose name will likely always be more associated with spy thrillers than ornithology.

I recently caught up with Wright for a Q&A about Bond and the book.

Q: The real James Bond came from what might be described as an East Coast aristocratic family, yet his birding adventures and his humble demeanor would have never let on to that, in my opinion. Would you agree?

Jim Wright: The real James Bond was a bit more odd than humble, with a difficult childhood. Although he came from an extremely wealthy family, his youth was marked by tragedy. His older sister died when he was young, and his mother died when he was around nine. His father moved to England. Bond and his brother went to a British boarding school, where he was teased about his American accent. Bond eventually studied at Cambridge, and his father wanted Bond to be a banker, but Bond wasn’t cut out for it. He became a self-taught ornithologist instead, and loved researching and writing and the birds of the West Indies. I recently saw a signed copy of the first edition of Bond’s Birds of the West Indies up for sale for $12,000.

Q: It’s hard to fathom what it must have been like traveling by sea to the Caribbean and South America repeatedly in the early 20th century. Those voyages alone must have been incredibly arduous, correct?

JW: The trips were tough for two reasons. Bond got seasick easily, and it was difficult to study all those birds of the West Indies when he had to travel by boat from island to island. Bond also lived on a shoestring. He often traveled by mail ship to the Caribbean, and then went from island to island on rum runners and banana boats.

One of my favorite Bond stories was when he went to Jamaica for the first time and was denied a permit to collect a certain rare pigeon. He returned the next year, posing as a tourist, and was told he could shoot as many of the pigeons as he liked.

Bond was an excellent shot but typically collected only a small number of birds he considered rare. I admire resourcefulness and determination.

Q: You describe Bond observing and studying birds in some very rough conditions, surviving on meager rations in hot, bug-infested environments. It’s likely ornithology today would be very different, especially his collecting approach.

JW: I imagine that exporting birds for scientific purposes or any purposes might be more restrictive. I doubt modern ornithologists can walk off a ship or plane carrying a shotgun like Bond did. One ornithologist I know, who had met Bond, was actually brought in for questioning on a Caribbean island under the suspicion of spying.

Q: There are so many paradoxes in this book. Bond is not a spy but a birder. Ian Fleming lives at a place in Jamaica called GoldenEye, that’s not named for the duck species but for an American novel and World War II. What surprises did you encounter in your research?

JW: I was often surprised by Bond, and how wealthy his family was when Bond was growing up. His father was a founding partner of a brokerage that later became part of Smith-Barney, and his uncle Carroll Sargent Tyson—who got Bond to become a birder—was so rich that he once owned one of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers paintings. After Bond’s father remarried when Bond was barely a teen, the second wife eventually got most of the family’s wealth, and Bond lived rather miserly and as a bit of a loner for more than two decades.

Bond was an important ornithologist because of his decades of research in the West Indies, and rued the unwelcome 007 connection that came as a surprise later in his life.

Q: One of the best moments of the book was Bond’s visit to GoldenEye to meet Fleming for the first time. It would be harder to drop in on a celebrity unannounced nowadays, wouldn’t it?

JW: Absolutely. These days, security is way tighter, and for good reason—although you can still visit GoldenEye for lunch, which is a treat. I saw birds there that were in Fleming’s 007 books and short stories, including grackles (The Man with the Golden Gun) and kingfishers (“For Your Eyes Only.”)

Q: Tell us about some of your other birding pursuits.

JW: I’m very excited about my latest book, The Screech Owl Companion, which comes out on October 17. I wrote for everyone who loves screech owls—especially those who want to attract one to nest in their yard. My co-author Scott Weston designed a revolutionary squirrel-resistant owl box, and we include plans on how to build it and advice on where to put it.

I am also proud of the images in the book, from classic paintings of screech owls by Audubon, Fuertes, and Roger Tory Peterson to incredible photos of screeches and other owls. Timber Press did a beautiful job.

I’ve developed a blog for the book, screechowl.net, and plan to include info on where I’ll be giving talks and how to order a signed copy.

If you liked this post, you also might like…

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post about the real James Bond, click the like button below.

Great story about the real JB, the West Indies ornithologist - so much more interesting than the film character! Thanks Bob for this informative post!