The domino effects of the Indiana isolated wetlands bill

A recently-passed bill renders much of Indiana’s wetlands vulnerable to development with broad-reaching effects on everything from bird populations to flood mitigation.

About one quarter of Indiana was once wetlands. Yet a new law removes essential regulations that protect isolated wetlands and eases development restrictions. The bill, called SEA 389, was signed into law on April 29, 2021, by Gov. Eric Holcomb, despite a swell of bipartisan pushback from many environmental and wildlife protection organizations. This wouldn’t be the first time Indiana has removed essential wetland protections, dating back to draining what was once the largest inland wetland in the United States, the Grand Kankakee Marsh.

The new bill concerns the repeal of a specific set of regulations put forth in 2004 that comprise some 800,000 acres of isolated wetlands. The wetlands were not protected by the federal Clean Water Act. Rather they were regulated at the state level, according to John Ketzenberger, Director of Government Relations, The Nature Conservancy.

The bill’s effects may render 80 percent of Indiana’s wetlands unregulated, according to the Indiana Department of Environmental Management and a statement issued by the Hoosier Environmental Council, due to the complete repeal of protections for “Class I” wetlands and a significant reduction of protections for “Class II” wetlands. The former is defined as an isolated wetland where over 50 percent of it has been “disturbed” by human activity, resulting in over half of its vegetation being non-native or invasive (Barnes & Thornburg). As a result, the wetland provides only minimal aquatic and/or wildlife habitat, and does not provide “critical” habitat for endangered species. A “Class II” isolated wetland is a wetland that would meet the definition of a “Class I” wetland, if it were not an ecologically rare or important wetland (Isolated Wetlands, 327 IAC 17-1-3).

Previously, property developers, farmers, and landowners had to go through a complex state permitting process if they wished to develop land that included the presence of an isolated wetland. With the new bill, landowners may be able to bypass this process entirely, as long as they can prove their wetlands are not connected to bodies of water that fall under federal control and thus benefit from the Clean Water Act.

Given that individual permits won’t be required for the development of any “Class I” wetlands and for smaller “Class II” wetlands, costs should be reduced for farmers and landowners. The process for proceeding with such development should be significantly streamlined with the emergence of new forms and policies, and a new task force that will release a report and recommendations regarding state wetlands in November of 2022.

Leaving this much of Indiana’s wetlands unprotected by making it easier to develop adjacent land could have significant effects on the state’s water quality, flooding mitigation, and bird populations, according to Brad Bumgardner, Executive Director, Indiana Audubon Society. “Wetlands purify the water, provide flood control, and provide an interconnectivity with all other habitats and wildlife species,” Bumgardner told TWiB in a written Q&A. “The health of Indiana's ecosystems determines the health of the inhabitants of the state.” Bumgardner said that Indiana’s wetlands support the most potent concentration of native bird species in the state, and that two-thirds of Indiana’s threatened and endangered bird populations are dependent on the wetlands for habitat, shelter, food sourcing and protection.

Species that are especially vulnerable to the loss of Indiana’s isolated wetlands include King Rails, Virginia Rails, American Bitterns, Least Bitterns, Marsh Wrens, Black-crowned Night-Herons, Common Gallinules, and Least Terns. It’s additionally troubling that migratory birds that depend upon the wetland habitat as key stopover sites on their spring and fall routes—some flying as far as the Arctic and South America—could be deeply affected by this bill.

We already know wetlands play an incredible role in mitigating floodwaters, which will be increasingly key as the effects of climate change, such as the more intense and frequent storms currently taking place across the globe, continue to worsen. One way this plays out is that ephemeral streams, dry beds that are filled with water after a heavy rainfall and which are formed during bird migration season, will lose their protected status as well, meaning that dredge and fill activities will be permitted. According to Ketzenberger, this will have a detrimental effect on the remaining wetlands, negatively impacting hydrology and the ability of wetlands to curtail floodwater overflow. Losing control over floodwaters often puts clean drinking water in harm’s way, where water systems can become contaminated with storm runoff, pollutants, and bacteria, affecting both humans and wildlife alike.

Ketzenberger expressed concern that the increased costs and resources it would take to ensure a safe water supply for everyone would result in a burden that would be passed down to taxpayers and lenders, ratcheting up the price of water treatment for communities. Clean-up after flooding can range from a nuisance to a devastating event and Ketzenberg fears that in those cases, the cost would be passed onto the community as well. “Wetlands are central to The Nature Conservancy’s clean water strategy,” he said. Echoing him, Bumgardner said that the bill was in direct opposition to the work of the Indiana Audubon Society.

With so much at risk, from bird populations, to clean water supplies, to statewide flood mitigation practices, its heartening that a massive community outcry regarding the bill has raised awareness of the wetlands and the importance of their protection with over 110 signatories mobilizing around a letter to the governor, asking him to veto the bill. Despite being unsuccessful, the groups will continue to work together. “They’ve remained in contact and are working to find new ways to collaborate and capture public sentiment that clearly favors protection for the isolated wetlands,” said Ketzenberger. “We’d rather have defeated the bill, but we hope to capitalize on this silver lining.”

Piping Plover Pale Ale is back on Sunday!

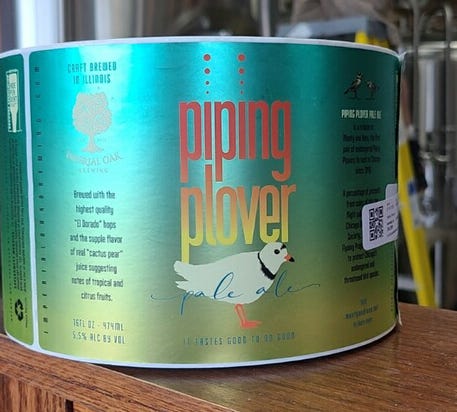

Imperial Oak Brewing will again release Piping Plover Pale Ale, this time Sunday, Aug. 1, at 12 p.m. at its location in Brookfield at 9526 Ogden Avenue. This top-flight ale, a tribute to beloved Piping Plovers Monty and Rose, features the highest-quality El Dorado hops and the supple flavor of real cactus pear juice, suggesting notes of tropical and citrus fruits. The beer will be available in cans or for enjoyment at the tap room. Last year’s release sold out in just a couple hours.

Designer/illustrator Bill Fogarty has again created wonderful artwork for the beer’s label. The cactus juice is a tribute to the cactus that is a resident of Piping Plover habitat from Montrose to locations around Lake Michigan. Proceeds will again benefit the conservation and education programs of the Chicago Ornithological Society. We hope to see you there!

This TWiB post was emailed to the free list as well as paid subscribers. You can ensure you never miss a post by becoming a paid subscriber for $7/month. By becoming a paid subscriber, you support local storytelling and advocacy for birds and their conservation, while covering a portion of the costs of creating this newsletter each week.