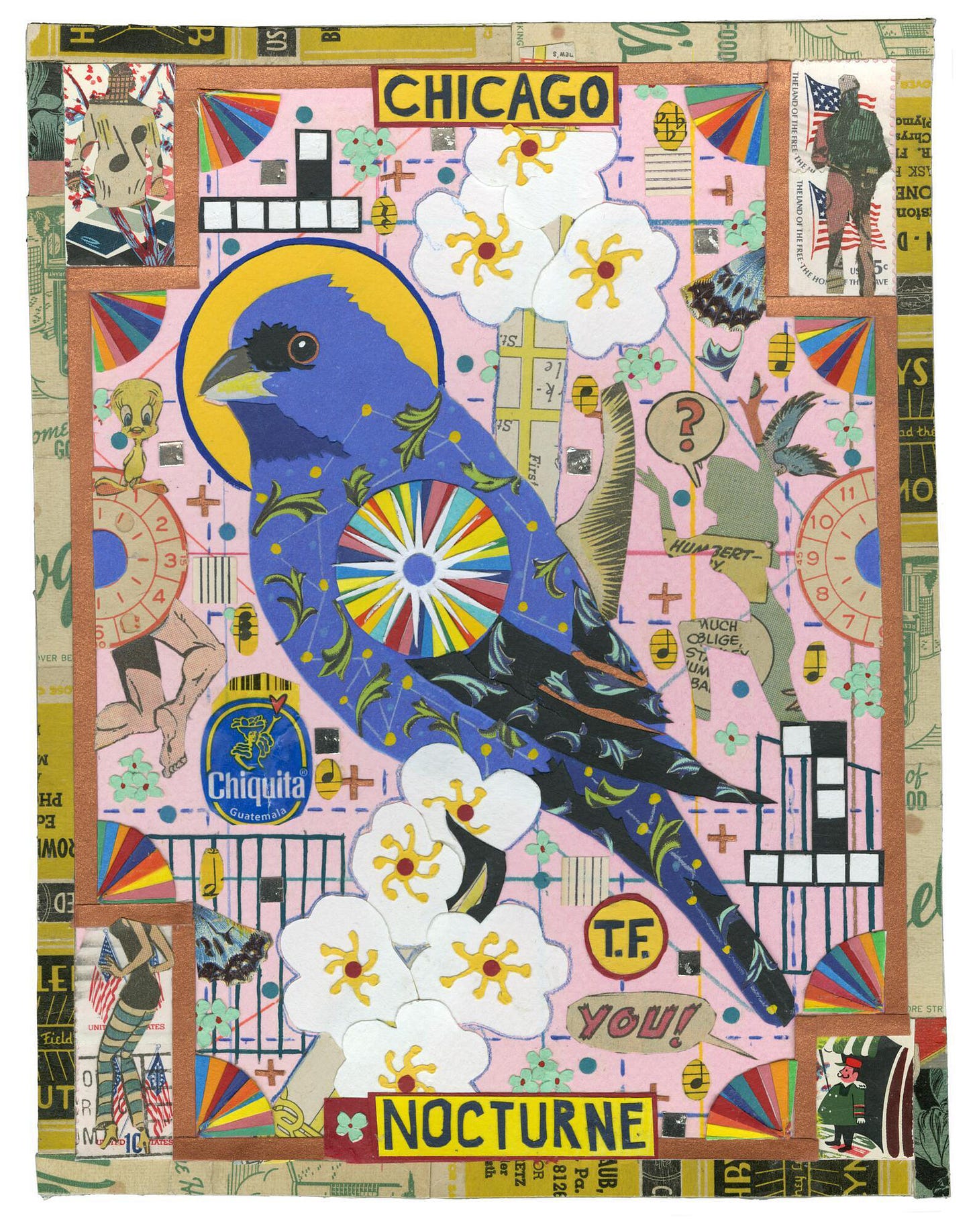

The Birdman of Chicago

A tribute to Tony Fitzpatrick.

Sometime in 2020, I was fortunate to visit Humboldt Park with artist and Chicago icon Tony Fitzpatrick. He was there with some friends, going for a walk and feeding the ducks and geese.

Going to Humboldt Park was for Tony the equivalent of going to Yellowstone for most people. The park’s not really what you’d call wild, but that didn’t matter to Tony. For so many city dwellers, the park is a place to breathe, unwind a bit and maybe have a barbecue. Go down to the lagoon and chop it up while feeding the mallards.

Let me preface this by saying Tony and I weren’t great friends. And so this isn’t meant to be an obituary. I’ll be the first to say I didn’t really know him that well. I only benefited from his generosity and absorbing some of his world view.

I met Tony the first time I attended a Birds & Beers event soon after quitting a job I was miserable in. I remember he was wearing a Baltimore Orioles cap appropriately enough. I heard him saying something about acting in a TV series, and I assumed that was his main profession. I didn’t know anything about his art at that time. Tony didn’t drink, and I later thought his presence at the event was mostly just because he liked being around other birders. He wasn’t a lister or chaser, or even an expert level birder, but I know he considered himself part of the birding community.

Around the time I was thinking about turning the Monty and Rose story into a documentary, Tony happened to go down to the beach and make a few social media videos. I reached out and Tony said he was willing to be interviewed and that I should stop by his studio sometime.

When I got to the studio with a hired videographer and even my 9-year-old daughter in tow, he didn’t seem to really desire an interview. Tony was so gregarious that it would be understandable if he couldn’t be available to everyone. I’m sure I came across as a bit of a geek anyway. I steeled myself to re-explain my project, hoping against hope that he wouldn’t decline an interview. But soon enough we were seated in his small gallery space and recording his comments. By the end, he made a few encouraging words to me off-camera.

As my film made its debut, it was clear that Tony’s comments were among the highlights. After showings people would say, “How did you get an interview with Tony Fitzpatrick?” I realize now that my naïveté as a filmmaker might have benefited me. But also Tony had a soft spot for fellow birders. As I’ve read tributes to Tony in recent weeks, several have noted that he always made room for newcomers and people outside the mainstream. Fred Sasaki of the Poetry Foundation had this to say:

“Tony was a champion of freaks and misfits, which was a huge part of his big bear embrace of artists and creatives in Chicago. Tony held the door open for so many outsiders looking for a start in art. He was many things to many people, and without question a poet at heart. I feel blessed to have experienced his friendship and the great work we did over the years. He will be deeply missed.”

A few months later, I asked Tony to record a social video for a new campaign I was involved in. I was thinking he’d go along with it and with a big following might give us some free PR. But we never really could make that happen, and I think in part it just wasn’t his thing. It was the first of many times I observed that Tony had his own standards and didn’t really compromise. Those were traits that one has to appreciate and admire. Some have placed Tony on a sort of Chicago literary Mount Rushmore with Nelson Algren, Studs Terkel, and Mike Royko—not exactly a crew that dabbled in fluff. In the words of rock critic Greg Kot, “Tony was the birdman of Chicago. A visual artist, an activist, a poet, an actor, a playwright, an organizer, a catalyst.” Kot noted Tony’s collaborations with the singer-songwriter Steve Earle.

Soon after my film debut, Tony did agree to appear on a virtual panel that I held in partnership with a birding publication. I wasn’t sure if he’d attend until his profile popped up on the Zoom. I was a bit nervous as about 200 people from all over the country were on the call. Tony always spoke his mind, and his acerbic answer to a question about plover conservation—that the wildlife officials were “a bunch of jackasses”—sticks with me. Tony didn’t have patience for politicians or bureaucrats. The reality is that the environmental movement might benefit if more people followed Tony’s lead and dispensed with pleasantries.

The second version of the Monty and Rose film—a feature-length documentary—came out a few months later. One of Tony’s quotes in that film always brings down the house in screenings. I’ve presented the film in a variety of settings, including faraway states that don’t really know anything about Chicago or plovers or Tony, and this one comment always generated spontaneous laughter.

So here’s the quote, though one really has to hear it in Tony’s voice for its full effect. At this point in the story, a large multi-day music festival expecting 25,000 people is threatening the plovers’ nest on the beach. Said Tony:

“Had that [festival] happened, I had a motorcycle club, that shall go nameless, and they were going to send a hundred soldiers, and we were going to guard the perimeter of that nesting site. And believe me you, buddy, nobody would have violated that nesting site.”

I was out of touch with Tony for a couple years, but I know he read my newsletter and would occasionally write with some encouragement. “Nice one, pal,” he’d say. In one of our later conversations, we talked about the plover phenomenon and he offered me some compliments. Again, he was generous with praise.

Then an opportunity emerged to add one of his works to the Newberry Library’s collection. It would be a first to have one of Tony’s collages in the 138-year-old institution (where I work). A couple of colleagues and I went to visit him in his new studio on Damen Avenue. It was around Halloween, and he was working on a drawing of Frankenstein. A Blue Grosbeak collage titled Nocturne caught my eye. Blue Grosbeak is a species once found at Bell Bowl Prairie. That piece would end up in the exhibition, and a photo of it accompanied Tony’s Chicago Tribune obituary (also see the top of this newsletter).

While at the studio, we were complimenting a black-and-white drawing on the wall. “Why don’t you take that one, too?” he said. The work’s now in the Newberry’s possession today and available for generations to come.

The last email exchange I had with Tony was about sparrows. I’d written a piece about the fight over House Sparrows that took place in the 19th century. There’s still a lot of venom thrown sparrows’ way today. House Sparrows are not birds that anyone is going to seek out or celebrate. But most anyone who enjoys and appreciates birds can admire their tenacity. It’s a reminder that the joys of birding are often found in the everyday, at places like Humboldt Park.

People need to stop being Dicks about the Sparrows... particularly Birders... it is petty and vindictive to attempt to discern which birds get to remain in the world...

When Birders do this?

We look like assholes...

What a wonderful article! Montrose Bird Sanctuary is my favorite place in the world. We enjoyed your films and love your newsletter. And we love sparrows too, they are such an interesting tribe.

As a teen he would nurse injured hawks back to health as I witnessed walking home with him to see his latest patient…@one point caddying for a woman golfer with one on his shoulder as she recalled ‘ My caddy cloths& my clubs were covered in bird droppings!’ Now that’s an unapologetic ‘Bird Man’ The last time we met was@ his studio, he doing wine bottle labor designs & a collage.Some music band wanted him to create an album cover but didn’t want to pay his standard pricing, So he tells me that they hired an Artist in Chicago that mimic his work for not much of a fee. As I asked what should she be doing as an artist He said ‘Adding something new to what she’s seen in my work& everyone else’s Art she’s ever viewed that would be creative’ Tony would have appreciated your honest vouce in this article…as do I