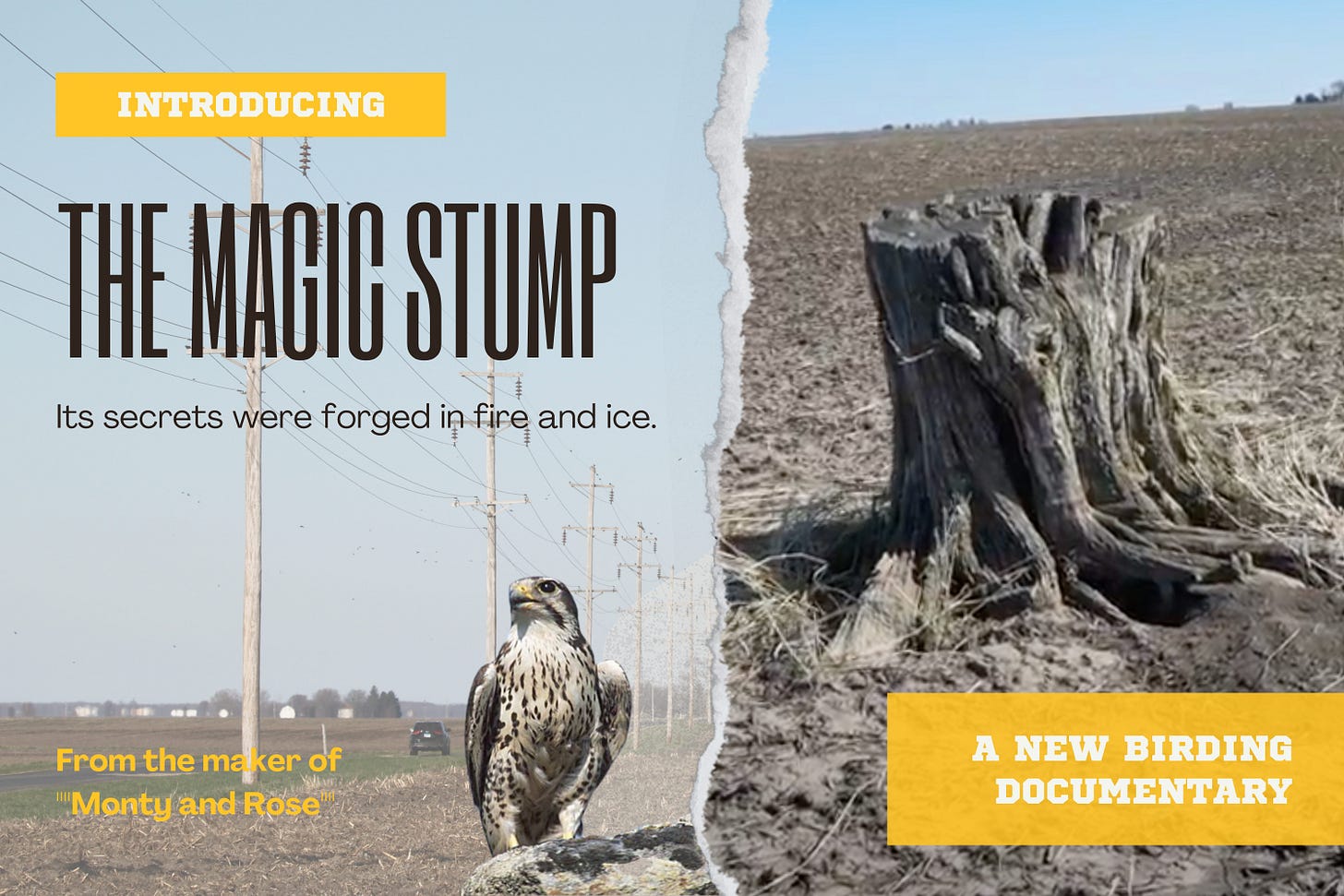

Stump is magical again: Prairie Falcon returns for 14th year

Single stump in a farm field remains a mysterious wintering locale.

It doesn’t take much for humans to be welcoming to nature. In this case, it’s leaving a lone tree stump—the only tree within a single square mile.

Earlier this month, on November 2, an old friend greeted Tyler Funk when he visited the so-called Magic Stump. It was a Prairie Falcon that may be the same bird that’s been in the area each winter since at least 2012.

“I got my welcome back flyover while setting up the camera,” Tyler reports.

If you don’t know about the Magic Stump, let me quickly explain. A chance encounter with a Prairie Falcon years ago led to the discovery that it was spending each winter in east-central Illinois. If that wasn’t remarkable enough, the bird repeatedly used the same Osage Orange stump as a perch and roosting location. Soon enough a second Prairie Falcon joined the first one. At least one falcon has been wintering in the vicinity of the stump ever since. To put this in perspective, the number of Prairie Falcons seen east of the Mississippi River each year averages in single digits.

Tyler’s placed a trail camera facing the stump, with permission from the property owner (the stump’s on private land). He’s captured some beautiful video of the unsuspecting falcons, as well as many other species including Northern Harrier, Rough-legged Hawk, Snowy Owl, and Short-eared Owl, and mammals including Mink and Coyote (more on mammals in a minute). It’s not just the stump itself, though, there’s something almost eerie about this vast farming area that stretches over many square miles. Located on an old glacial boundary, the place is a raptor magnet. A Gyrfalcon, a scarce Arctic species, has shown up in the last decade in separate years, both times alighting on telephone poles on the same road.

This is the story of humans, birds, and that single stump. People transformed the land around the stump for agriculture more than a century ago. The stump was part of the transformation, with Osage Oranges or hedgeapples often planted as natural fences. In winter, the land resembles a short-grass prairie or steppe. Just to the liking of birds like the Prairie Falcon. And as time went on, natural hedgerows were removed to allow for more crops.

My last visit to the area took place in December 2022. But I checked in with Tyler just recently to see if I had my departure and arrival dates correct. That winter, a falcon was likely last seen on February 24, 2023. Then a falcon returned and was first seen on October 28, 2023. It stayed through the winter, departing on February 26, 2024. How it knows when to arrive and depart remains a mystery. As does where it spends its summer across the vast Prairie Falcon territory of western North America. Whether the bird actually “knows” Tyler remains a mystery, too, but it does seem to appear when he appears.

And, about those mammals. A bobcat became the latest species to show up on the stump, creating this stunning image.

I began visiting the stump in 2021 and eventually made a 20-minute documentary short about it (see below). Earlier this year a reporter with NPR’s Radio Lab visited the stump and created a piece for the Terrestrials podcast. Tyler’s article in a 2017 edition of the Meadowlark journal provided the most thorough summary to date.

There are no guarantees a Prairie Falcon will return to the stump each year. It’s a long flight from the breeding grounds, and a bird could go to any number of places in winter. In addition, a falcon at 12 or 13 years of age is at the upper end of its longevity. We don’t know what year might be the last, or if another falcon shows up to take its place—another mysterious possibility. But at least for now, it’s another winter of the falcon at the Magic Stump.

If you’d like to watch my documentary, click the button below. It’s now available at no cost.

An unlikely alliance

The neighborhood Blue Jays were making a racket as I took a stroll through an area forest preserve. This was more than the usual cacophony, and there were five of them so it seemed an avian predator might have been in the area. They surrounded a tree cavity that was about 30 feet off the ground. The first brave bird to approach the tree, though, wasn’t a jay—it was a Northern Flicker. A Red-bellied Woodpecker soon flew over toward the tree, along with a few American Robins. I’ve known these multi-species mobs to form on occasion, a sort of cooperation to defend against invaders, and twice now I’ve seen flickers right in the mix. The jays stayed back while the flicker peered into the cavity, which I believe harbored a screech owl. The birds stood stock-still for about 10 minutes before they began to wander off. If an owl was in there, it managed to stay well hidden.

Interested in a sticker honoring the Magic Stump? Reply to this email with your mailing address, and I’ll send you one in the mail. Thanks to Pam Sloan for this design.

If you enjoyed this post, you might enjoy this previous post:

Thanks for linking that documentary - what a fun watch! Here in DC we have a yellow-throated warbler that just returned to a golf course for what is now its seventh winter. Some local birders have started making t-shirts to commemorate it. I love the familiarity and the lore that develops around birds that regularly return to spots far outside their range. It feels like you actually get to know them as individuals!

Glad to learn about this stump!